The British Cultural Revival. Why It’s Happening. And How Luxury Brands Can Lead It.

While the news is full of discussion on immigration, cost of living and global politics, something is happening under the surface in Britain.

Young people who grew up with globalisation, streaming, cheap flights and the internet are turning back toward things that used to be seen as boring: Ancient history, craft, dialect, and local culture.

- They’re buying memberships to heritage sites. Membership of The National Trust among 18–25-year-olds jumped 39% in the last year. For heritage site visits overall, younger adults (18-44) are now more likely to visit than older generations.

- They’re rediscovering land. Walking trips in England increased by about 10% since 2019. Approximately 25 of British people use the identity of a “hiker”. Foraging, wild swimming are more popular than they were in my great-grandma’s generation. Interest in “foraging” rose more than 300% on TikTok between 2020–2023.

- Heritage craft apprenticeships are at a 20-year high. Blacksmithing, wood carving, stone masonry, weaving and ceramics are all rising. Traditional crafts searches have grown steadily every year since 2020.

- Books about folklore, myth and British history have surged in sales, led by women aged 20-40. Folk horror, witchcraft history, English myth and rural storytelling dominate charts. TikTok reports 270% growth in hashtags like #BritishFolklore, #EnglishMyth, #CottagecoreUK, #FolkloreRevival.

If you’re a British luxury brand, especially one designed and made in the UK, you should be sitting up and paying attention. You’re exactly the cultural material people are searching for.

Why luxury? Becayse luxury isn’t just nice things. As Kapferer and Bastien say in The Luxury Strategy, luxury sells identity. And British identity is being rebuilt.

This piece is about where that shift came from, why it’s happening now, and what UK luxury brands can practically do with it.

1. How we got here. 300 years of looking outward instead of inward

To understand the current revival, you have to go backwards.

Colonial Britain. Status through other people’s cultures.

In the colonial era, British “good taste” was built on importing other cultures.

If you were middle or upper class, you showed status through your indian textiles, Chinese porceain and tea, japanese prints and screens and Middle Eastern carpets.

Owning these things signalled that you were connected to empire and trade. Had money and reach. And we’re educated and worldly. This put you firmly above the local and working-class.

A Victorian woman who knew her Japanese prints and Indian fabrics would have been seen as far more sophisticated than a working-class woman in local wool or cotton. Taste was about proximity to global trade, not about British culture itself. So back then, being cultured meant being LESS locally British.

Even now, the foods we associate as quintessentially British; shepherds pie, fish and chips, stew and dumplings, are seen as working-class foods.

20th century “international chic” and the foreign mask

The 20th century doubled down on that. Media trained people to aspire to Nordic simplicity, Japanese philosophy and French dressing. In the 00’s it was high culture to know about Feng Shui, Bikram Yoga and to go on Ayahuasca retreats in South America.

Britishness, especially Englishness got coded as practical, class-bound (a holiday to Wales? = broke), dowdy and functional. And brands leaned into looking foreign.

Kapferer points out that when a culture loses confidence, its luxury brands try to look like they belong to another one. That’s exactly what happened here. Brands didn’t trust British identity to sell.

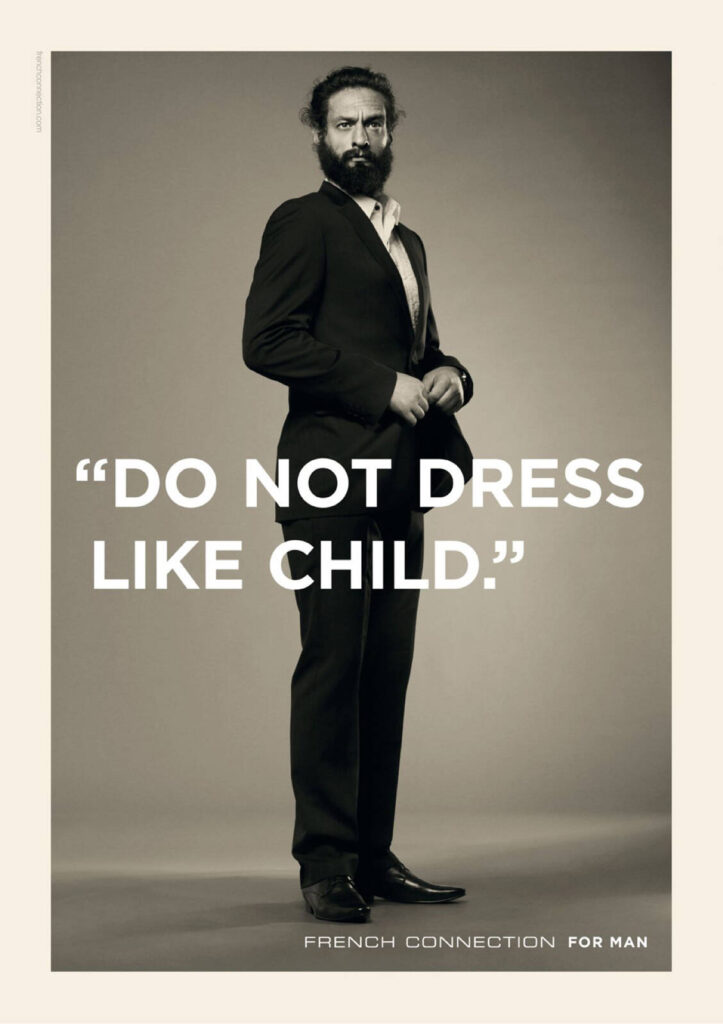

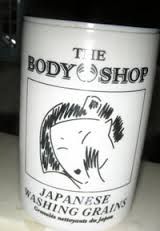

Think about the following brands which are 100% British

- Reiss. Founded 1971, adoped a generic international fashion house aesthetic in the late 90s.

- French Connection. Founded 1972. Framed itself as a French fashion label in the Mid 90s – 00s.

- The Body Shop. Founded 1976. Used Pan Asian/ Amazonian World Bazaar aesthetics in the 90s-00s.

- Pret A Manger, founded in 1986. Styled itself as a French Cafe. Cafe Rouge did the same.

- Bella Italia, Ask Italian, and Zizi. Also British. You may wonder if any of these euro resturaunt chains were founded by French or Italian people in the UK? The answer is no.

21st century. Cultural appropriation and the “what’s actually mine?” moment.

In the 21st century, the conversation changed. The internet made it easier for us to hear to opinions of the women who have actually grown up with Yoga as a spiritual practice. People who live in the countries the UK colonised.

We started hearing things like, maybe White British women shouldn’t say “namaste” at yoga classes. Maybe using hindu statues as garden decor is disrespectful. Maybe a lot of what we took under colonialism wasn’t shared. Maybe some communities want to share and some don’t.

There was a corrective. The idea of cultural appropriation went mainstream. And suddenly a lot of British people, especially white British started to pause, and have a think.

During a church hall yoga retreat and “gong bath” with my mum, I started to notice that I felt absurd. I was encouraged to chant in some kind of eastern language, which I suppose could have been hindu or bhuddist… I didn’t even know. But I thought to myself, these words mean something to the people who speak this language, I don’t understand this language. So I’m not going to chant it, but also…. isn’t there anything from my culture that I can chant to help me clear my mind?

It’s then that I remembered I had chanted growing up, with beads called rosary beads. Growing up in my catholic childhood, I had experienced ritual and sanctuary. Why is it considered better for me to chant with beads from a dififerent religion than the one I grew up with? What made it more special and more spiritual just because it was foreign? It felt like I’d been sold a replacement for something that wasn’t really broken. I could be doing this in a local church for free. I’d lost a part of my own culture and diluted someone elses.

Many british people started to ask themselves similar questions.

- What’s actually mine?

- What are my rituals?

- What are our old stories?

- What was here before empire and global wellness trends?

This is the engine behind the current British heritage revival.

2. Why the British revival is happening now

There isn’t just one cause. There’s a stack.

Hyper-globalisation and the flattening effect

For about 20–30 years, the story was be a “global citizen”, move freely, don’t get attached to place, accents and roots are baggage.

“Cosmopolitan” was an ideal identity.

Then the internet turned that mindset into a daily reality. Everyone (in the western world, not just UK) watched the same shows, wore the same brands and used the same slang.

The internet created a world where you could access everything, from anywhere, instantly. But the side effect was that nothing felt like it truly belonged to you. Culture got flattened. Everything started to turn into sameness and internet slop. And young people felt that loss, even if they couldn’t explain it.

On top of that, we had a long phase where it was fashionable to say Britain has no culture, our history is just shame and guilt. And whether or not it was meant literally, it has likely been internalised.

The pandemic broke the illusion that modern, urban, global life is stable and desirable. People suddenly saw how fragile our systems are and how quickly normal can vanish. In that kind of shock, people look for what lasts. Landmarks, long standing rituals, crafts that survived multiple wars.

Luxury works when it feels anchored in time, not in the latest trend. “Luxury loves time.” Culturally, that’s now true beyond luxury. People in general want things that feel like they’ll still matter in 30 years.

Climate anxiety. Turning back to land and seasons

Layer climate crisis on top. If you genuinely believe the future might be worse; harsher weather, food insecurity, ecological collapse, you start looking for connection with the land that’s still here.

That shows up as hiking and wild swimming booms, interest in traditional farming and gardening and fascination with British Wildlife. We’ve also seen older seasonal customs returning such as solstice, harvest etc.

Multicultural mirror. “If everyone else has culture… do I?”

In a multicultural country, you see communities proudly practising and protecting their culture. Somali, Pakistani, Polish, Indian, Caribbean, Nigerian, Romanian, etc. This naturally triggers questions.

What did my family used to do?

What did we lose to modern life?

What is English culture outside the empire story?

People want belonging and memory.

3. Why this matters so much for luxury

If this was just a lifestyle trend, luxury could ignore it. But it isn’t. It maps directly onto what luxury is for.

Brands with Luxury strategies should:

- Sell meaning and identity over function.

- Be rooted in a specific culture.

- Love time and feel like it has a past and a future (getting better with time).

When brands delocalise and chase global sameness, they slide into premium, not luxury.

Right now, British culture, land, craft and heritage are being revalued.

So if you’re a British luxury brand with products designed and made in the UK, you have exactly the kind of meaning that both British and global customers are looking for. Made in Britain still carries weight at home and abroad.

4. How UK luxury brands can lean into this revival (without being political)

Product & design. Make things that actually belong here.

If you’re designed and made in Britain, use that.

- Use local materials where possible. British wool, leather, wood, stone, metals.

- Reflect regional influences. Scottish mills, Yorkshire stone, Cornish light, Cotswolds limestone, Welsh mountain colours.

- Design for time. Pieces that patina, improve with age, can be repaired, can be passed down.

Tie products into British seasonal and cultural rhythms such as Harvest, Michaelmas, Advent and Christmas.

Story & positioning

Your brand world should show the specific place your brand stands in, the craft lineage you sit in and the people making the products. Show craft as a serious and time heavy practice.

Visual language

If your brand imagery could have been shot in any city in the world, it’s not using British identity properly.

Shift your visuals to include weather, landscape, architecture, texture. This isn’t about Union Jacks, just make sure someone looking at your brand can recognise this comes from a specific place.

Marketing & content

Lean into education and storytelling. Try short videos explaining the origin of a fabric, cut, scent or pattern. Stories about the region your workshop sits in with real local detail. Posts that link products to reasons rituals or old customs.

To really position something as British luxury, if you can, show an old version of your product that’s still in use. For example, nothing would show the luxury of a Barbour jacket more than a young girl wearing it and maintaining the wax even though it is a hand me down from a grandparent.

Experiences

People are tired of everything being virtual.

If you can, build open workshop days, seasonal events, walking routes, small group craft sessions and talks on local history and materials. Partner with the National Trust, English Heritage or Craft Schools.

Hold your line, don’t chase every trend

Don’t dilute your brand with cheaper, trend-led ranges that contradict your “made to last” message. Don’t constantly do “global collabs” just to look exciting. Don’t strip out all Britishness to appeal to a generic international customer.

Paradoxically, being more specifically British will often increase your global appeal.

People abroad aren’t buying you to get a generic lifestyle. They’re buying you to get a piece of this place.

What “designed and made in Britain” really signals now

When a product is genuinely designed and made in Britain, and you can show that honestly, it signals a few things at once.

To British customers you’re showing that you’re investing in local jobs and skills, you care about the community you’re working in and there is likely minimal exploitation in your supply chain.

To international customers, you’re offering a exotic item that they can’t get locally. Your British wool cardigan IS the hand printed Japanese wallpaper. French people don’t want to buy British immitations of french products. It feels different and special and that is exactly what luxury is supposed to be.

After decades of global sameness, culture confusion, shattered security and a shaky future, the British cultural revival is putting some ground under the feet of young people in the UK. Luxury is one of the few industries perfectly positioned to respond, because it already knows how to work with time meaning and identity.

If you’re a British luxury brand, especially one designed and made here, the opportunity is clear. Committ to showing your heritage. That’s where the next decades loyalty, pricing power and cultural relevance will come from.

Leave a Reply