Inference – A forgotten part of cognitive fluency

It’s not the cleverest campaigns that convert the most. It’s the ones that feel effortless, are clear and emotive.

Not effortless to make, but effortless to process.

If someone has to work at understanding your message, you’ve already lost them.

However, a lot of marketers don’t get this.

We’re usually above average communicators. Marketers typically loved writing as a kid, which probably developed through a love of reading. When I was a teen, I loved magazines like The Sunday Times Style and Mizz and Elle and all the rest of it. I’d study the articles and how they were written and write my own pieces. As an adult, I love Wired, New Scientist and am a literature obsessive.

If you’re also a lover of literature snob and prefer Booker Prize winners to Best Selling romance or thriller novels. Then you’ll probably enjoy your cognitive fluency being challenged. Unique vocabulary and sentence structure. With lots of opportunities to read into the plot, characters and references. Many literature is ambigously symbolic, allowing for discussions about politics, religion, or what not.

Or maybe you like indie films where there’s more of the same, a strangely structured plot line. A scipt without cliches.

If you have a high processing level, unexpected things, complicated things, symbolic things are all fun.

But not many people have a high processing speed. And for those of us who do have it — you’ll know that it comes and goes. I can’t always stomach a book of any kind and even though I watch an indie film from time to time, the majority of my viewing is Netflix’s Love Is Blind. After working all day with you guys, and then looking after my kids, I feel like an outdated computer.

And so when it comes to my 9pm shopping binge, I’m not going to understand much about your website, just take my credit card.

What is cognitive fluency?

Cognitive fluency is the brain’s way of saying, “This is easy to process.” When something feels easy to understand, we trust it more, remember it longer, and are more likely to act on it (Alter & Oppenheimer, 2009).

Studies show that people are more likely to believe statements that are written in easy-to-read fonts (Reber & Schwarz, 1999). Fluency influences not just understanding, but also judgment, risk perception, and even moral decisions (Alter et al., 2007). We trust people more when we understand what they’re saying.

Now marketers already know that when writing copy we need to use short sentences, short paragraphs and short words. Keeping the vocabulary we use as clear and simple as we possibly can. But there’s more to fluency than literacy and vocabulary. It’s impacted by layout, tone, format, audio clarity, emotional context, cognitive load and cultural familiarty.

So even on your TikToks (especially on your TikToks) you need to be aware of cognitive fluency.

Let’s examine this in more detail:

What is inference?

If you’re British, like me, you’ll probably love an inferred joke. One that doesn’t expressly say the punch line, something people have to work out for themselves. Even better if it’s discreetly insulting.

We love metaphors, sarcasm and cultural codes. This is actually a skill that not everyone has. Most people don’t get inference unless it’s spoon fed to them. Especially in spoken content. On TIkTok, Reels or Live content, inference is harder to decode. Listeners can’t re-read or pause to reflect, and they’re often multitasking. According to the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC), 18% of adults in England and 21% of adults in the U.S. have very low literacy skills (OECD, 2023; World Population Review, 2024).

Inference is the ability to understand what’s implied rather than stated. It includes:

- Picking up on tone, metaphor, sarcasm, or bias.

- Connecting the dots between ideas.

- Drawing conclusions based on context.

People have differing levels of ability when it comes to understanding inference

People at Level 1 or below on the PIAAC scale struggle with:

- Making basic connections between two ideas

- Identifying main points in short texts

- Understanding implied meaning

Even Level 2 adults (the median in the UK) can only manage low-level inferences, like:

“Sarah grabbed her umbrella before leaving the house” = it’s probably raining. Or “Mariah opened the recipe book and turned on the oven” = she is about to cook.

But more complex inference, like sarcasm, metaphor, or culturally-coded messaging, requires Level 3 or higher, which is about 44% of the US population.

Let’s look at level 3 inference skills:

“The article begins by praising the company’s green initiatives, but ends by questioning the source of their funding.” = The writer is skeptical of the company’s motives and may be implying hypocrisy.

To understand this, the reader needs to detech a shift in tone, catch the subtle bias.

“‘Sure,’ she said, glancing at the clock for the third time, ‘I’d love to hear more about your cryptocurrency hobby.’” = She is being sarcastic or impatient, she isn’t genuinely interested.

The mismatch in what’s said and what’s meant requires the reader to detect the tone, social cues and context.

And level 5:

“‘Of course, we all know how well that worked out last time,’ he said, as he signed the new contract.” = He’s knowingly engaging in something risky, and his tone is cynical and resigned.

To understand this, the reader needs to interpret sarcasm, implied context and internal contradiction all at once.

“The author begins by citing data supporting universal basic income, then introduces anecdotes from failed trials, before concluding that more research is needed. However, their choice of emotionally charged language when discussing government spending hints at a deeper ideological stance.” = A balanced structure is presented as subtly biased through framing.

If your content is too subtle, ironic, or dependent on context, you’re asking your audience to work too hard, and that’s where fluency breaks down.

If you’re writing at a level 4 or 5, you’re writing for your peers, not your customers, most likely. Just a tiny sliver of the population is at this level (about 1-2%) (OECD, 2023).

Writing for different inference skills

For Level 1–2 Be literal, clear, and step-by-step. Avoid idioms, metaphors, or satire.

For Level 3: You can use some tone and structure, but still clarify your point directly.

For Level 4–5: Use economy of language, subtext, double meanings, and even satire or ambiguity, as long as your core message is intact.

Inference can cause huge misunderstandings

If you’ve ever made a TikTok which you thought was straight forward but people took the completely wrong way, you’ll know what I’m talking about. Say for example you take one sitation and apply it to something else to examine it’s substance and ethics.

Eg “If someone walked into your living room and dumped a bag of litter in it, you’d call the police, yet that’s what we do to nature every single day”.

It can be misinterpreted by someone with level 1 or 2 inference skills in the following ways:

- Misinterpreting the literal meaning. “Wait, who’s dumping rubbish, is this about burgulars?” Because the analogy is too far removed from their every day experience with littering. They’ve gotten confused.

- They understand the first half. “Yeah that would be awful, but no one is actually doing that”. They understand the sentence in isolation but can’t connect the dots themselves.

- They focus on the wrong detail. “Well I wouldn’t call the police, I’d clean it up myself.” The person is stuck on problem solving the fictional setup, not engaging with the analogy. Their brain grabs the most tangible part and stays there.

- Emotional mismatch. Someone now feels attacked or confused. “Wait, I don’t litter, why are you comparing me to someone who’d do that in a house?” They can’t see the message, because empathy via metaphor feels too distant or morally exaggerated.

So you see, even when you as a person with high literacy skills can attempt to make something simple, you can make the situation worse.

Ground rules for keeping your audience with you

- Name the complexity, then clarify. “This is a layered issue, but here’s what matters the most.”

- Anchor the abstract in something concrete. Use clear examples, stories or sensory images. Show the principle in action before unpacking the theory.

- Don’t assume shared knowledge. Introduce references briefly.

- Even if it was ovious to you, say the thing. If your message comes accross as implied in any way, also state it explicitly: “What I mean to say is, unchecked bureaucracy can be harmful.”

- End with a clear takeaway. If your context explores complexity, give your reader (or listener) something to walk away with. A quote, a healine, a summary.

Let’s rewrite our sentence with these guidelines:

“If someone threw rubbish into your home, you would be angry. But people throw rubbish on the ground outside all the time. It hurts nature. It’s the same thing.”

Sentence level shifts

Instead of…. ” There are no easy answers.” Say….. “There are no easy answers, but here’s where I’d start.”

Instead of…. “The problem isn’t the police, it’s the politics of the policy.” say ” The policy may look fine on paper, but the way it’s used often reflects deeper power issues.”

Instead of “Of course, we all know how that turned out” say “(Spoiler: it didn’t go well.)”

Remember, inference is a privilige of attention. If your audience is tired, distracted or unfamiliar with your context, they’ll miss the subtle stuff. No matter how smart they are.

When to write for higher literacy skills

Notice how I’m talking to you like you’re kinda smart? That’s because this is a long form blog.

Once you’ve made your core message clear, high-inference content becomes a reward not a barrier. Think of it like layers in a conversation, you start with what’s shared, and then go deeper.

If you’re speaking to experts, founders or critical thinkers, nuance is a signal of respect. These readers expect layered meaning, intellectual references and moral complexity and may distrust messaging that feels dumbed down or oversimplified. Deep, layered content works best once people have already chosen to engage, not when they’re scrolling passively. So use it in formats people revisit:

- Long form blogs

- Podcasts

- Essays

- High context emails

- Lecture style video content

In branding, high-fluency language and inference-heavy tone signal luxury, exclusivity, intelligence and cultural fluency. This is especially true in sectors like fashion, architecture, strategy or boutique services.

If you want people to sit with an idea, to feel unsure or reflective, high-inference language does that. It slows people down, which is sometimes the goal, especially in advocacy, social commentary or thought-provoking campaigns.

When not to use high inference:

- In Call to actions or onboarding flows

- Signage or instructions

- Anything time sensitive or skimmable (email subject lines, tiktok hooks)

- Crisis comms

TL;DR

| Scenario | Use it? | Why |

|---|---|---|

| Long-form, opt-in content | ✅ Yes | Readers are choosing to go deep |

| Branding for a high-end or niche product | ✅ Yes | Signals sophistication and intelligence |

| Instructions, ads, TikTok hooks | ❌ No | Needs instant clarity |

| Email headers, alerts, buttons | ❌ No | Skimmed quickly. High fluency slows down processing |

| After trust & clarity are established | ✅ Yes | Advanced messaging lands best when the foundation is clear |

When to target high inference audiences

Sometimes the goal isn’t to include everyone. Sometimes you want to make your customers feel like they’re part of an elite gathering.

What’s the best way to do that?

Make smart people feel smart, and make others self-select out.

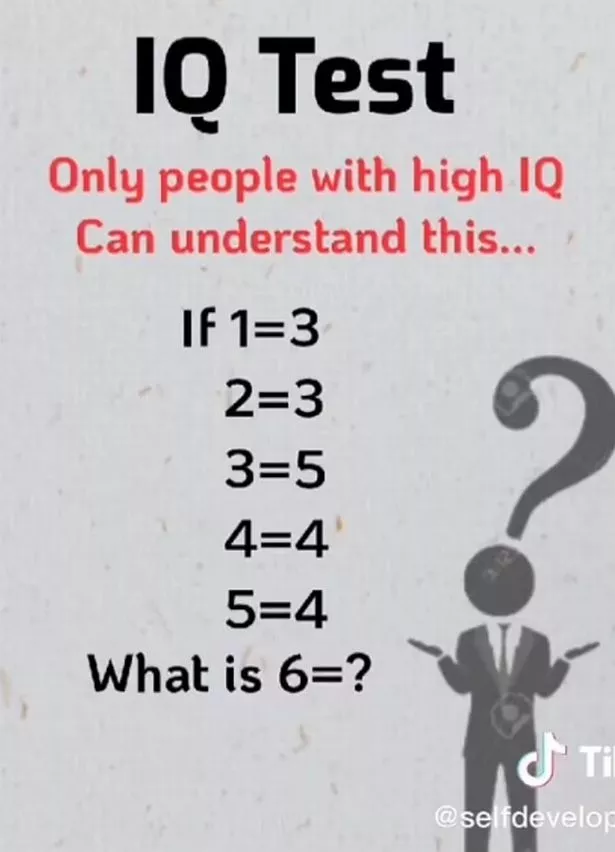

This can help you build prestige and exclusivity. Speak pride in recognition (“I get it”) and attract critically engaged thinkers. You could also potentially create virality with cleverness, people love to share things that flatter their intellect. Think of the ‘Share when you work it out’ memes we used to see lots of on Facebook. In it’s basic form, this is what many viral posts are.

Inference driven branding

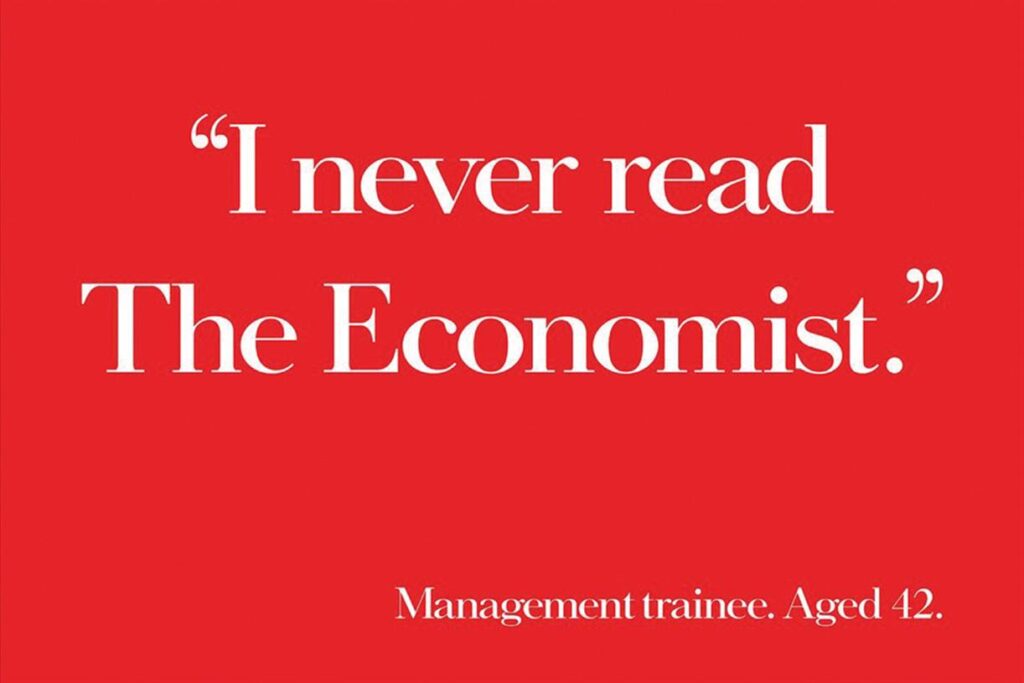

Some brands mainly use inference. The Economist being a perfect example. And you know, they really need to disqualify customers who have inference skills below level 2 early. So it’s an interesting strategy.

Their ads expect the reader to connect the dots themselves. Nothing is explained. The punchline isn’t in the ads, the reader supplies it. These ads are so clever because if you get it, you feel clever. You feel like you should be reading The Economist. It doesn’t even feel like the magazine is for people like you, it feels like you’re finally one of those people.

We talk a lot about identity led marketing up in here. And I feel like this is a great showcase of using inference to create an identity brand.

Inference tactics you can use

- Say less. Use minimalism to help your customer work it out for themselves.

- Imply meaning but don’t explicitly say it. Let tone, juxtaposition or brevity do the work.

- Smart readers love being invited to solve the meaning. Use wordplay, irony and inversion.

- Assume shared knowledge, but don’t require it for comprehension.

- Allow multiple meanings to exist.

Caveat: This approach only works when ambiguity is the point, not when clarity is needed. Use it in ads, storytelling, or brand identity, not in onboarding, legal, or product education. Remember at some point you’re going to have to let people know what it is they’re buying. We all already know what The Economist is, they already have strong brand awareness. They’ve got the awareness, don’t need to explain, and can now firmly inject themselves into someones self concept.

If you’re starting with poor brand awareness, have a go at trying spoon feeding it for people in one sentence, and using inference to find your people and disqualify your anti customers:

In conclusion, you can be clever, but learn where to put your clever ideas. And make sure you really understand where your audiences reading skills and attention commitment are at at any given marketing touch point.

References

- Alter, A. L., & Oppenheimer, D. M. (2009). Uniting the tribes of fluency to form a metacognitive nation. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 13(3), 219-235.

- OECD (2023). Survey of Adult Skills: England Country Note. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/survey-of-adults-skills-2023-country-notes_ab4f6b8c-en/united-kingdom_02bc78e4-en.html

- World Population Review (2024). U.S. Literacy Rates by State. https://worldpopulationreview.com/state-rankings/us-literacy-rates-by-state

- Nielsen Norman Group (2008). How Users Read on the Web. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/how-users-read-on-the-web/

- Reber, R., & Schwarz, N. (1999). Effects of perceptual fluency on judgments of truth. Consciousness and Cognition, 8(3), 338-342.

- Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive Load During Problem Solving: Effects on Learning. Cognitive Science, 12(2), 257–285.

- Reber, R., Winkielman, P., & Schwarz, N. (2004). Processing fluency and aesthetic pleasure: Is beauty in the perceiver’s processing experience? Personality and Social Psychology Review, 8(4), 364-382.

Leave a Reply